|

The Patients…

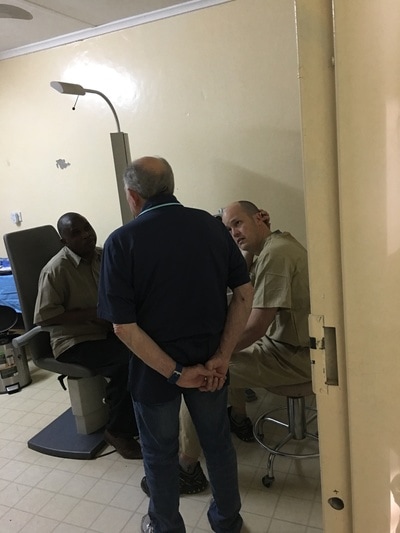

The patients in rural Africa are certainly different than any we’ve seen in the U.S. This should be expected as their lifestyle and culture differs from ours. This healthcare system does not practice much preventative medicine resulting in disease and ailments that are much more advanced than the majority seen in the West. Additionally, because we are providing free and very inexpensive care in a poor area, one can expect to see a different level of cleanliness. To boot it is very dusty here; an environment built on sand-like, clay dirt. The patients we’ve seen have a variety of ailments. We’ve seen damage to eyes from violence. We’ve seen glaucoma. Diabetic retinopathy is common. We’ve even seen many cases of very advanced squamous cell carcinoma, most commonly seen in HIV positive individuals, very rare otherwise. Most of the surgery performed is for cataracts. The clinic currently does not yet house any equipment to provide surgical retina treatments. Additionally, most of the diseases, especially the cataracts, are more advanced than of U.S. patients. As an example, cataract patients here visit a doctor when they are down to light perception and the cataract has become opaque and dense. It results in a more challenging surgery. Nonetheless, the patients are very eager for care and the clinic does their best to provide glasses that come close to the correction needed. There is a full staff at the clinic performing such duties as check-in, taking vitals, checking vision and a government funded position, “ophthalmologic clinic officer,” who sees patients all year. They also translate for patients who do not speak English, an essential service in area where Tonga and other dialects are the predominant languages. The first day is always a bit rocky as the staff and the doctors settle into their respective roles and western doctors get a handle on a third world clinic and its processes. As time progresses, however, both learn to communicate better with one another and do good work. This experience has advantages. Our boys received first-hand experience in working with patients – escorting to and from surgery, helping to draw up blocks (under supervision) and applying pressure to spread the block more efficiently before surgery. They were able to observe several surgeries, obtaining great exposure to a potential career in medicine. Additionally, our boys have been exposed to profound poverty and have had the opportunity to meet many friendly locals and learn about their lives.

2 Comments

On the afternoon of the second day our team was joined by another doctor, Dr. Samuel Verkerk. He is an ophthalmologist from the Netherlands and is currently serving in Macha, Zambia, about a 3-hour drive Northeast of Zimba. He arrived in January and is continuing for two and a half more years while he is developing an eye clinic. He hopes to find a Zambian ophthalmologist to train and to whom to leave the clinic. As clinic ended early this day we had time to walk through the surrounding community. On our walk, we ran into a patient, Ernest, who acted as our informal tour guide, generously giving us his time and knowledge. Ernest walked us through a “neighborhood” which is a collection of huts. One resident eagerly offered to show us his hut, which is an 8 foot by 8-foot room built of mud with a thatched roof. The only things inside this windowless room was a mat for sleeping and some sandals on a dirt floor. He also was excited to show us his pig hut, which had a thatched roof and was built of sticks, branches and any other materials he could find such as an old tire. Dr. Verkerk’s accompanied us on this walk. His time in this country proved to be a wealth of information about this culture, teaching us much about its male dominated family structure. As we continued, we passed many stands and small shops selling a variety of products from fresh produce to chips, soda and more items we could not recognize. We also passed bars, barbers, restaurants, butchers and more. Our tour guide showed us a primary school and the campus of a boarding school. We saw the soccer field where Ernest helps train a local team. The team had congregated to try to solve the problem of an air bladder protruding from the ball. On our walk, we were often greeted by a chorus of young children eager to practice their English, which would consist solely of “How are you?” Our reply of “Fine” and “How are you?” would initiate a gaggle of giggles. Everywhere we walked there was trash; pieces of plastic bottles, chip bags, banana peels, smalls boxes, shoe parts, wrappers and more littered on the ground. Most people burn their trash because they don’t have a garbage pick-up service. We are so accustomed to throwing our trash in a bag and having a service whisk it away to an unseen landfill. They don’t have this luxury, so the trash lies where they leave it. It makes us think about this culture as it adopts western products and their efficient delivery systems in containers such as plastic; how that may be a burden on an immature infrastructure; and, despite our mission here to bring western medical advances to the third world, we wonder if all of our western influences are truly advances that are good for all people everywhere. BLOG #2:

Our volunteer experience… The work done here is a function of the type of issues patients bring and the resources available. Flexibility is a must. Regardless, these people are welcoming, very friendly and appreciative. Patients are often already lined up at the door when we arrive. Some will spend the night on the porch outside the clinic in order to be seen the next day. In fact, one patient brought his mother two weeks earlier than our team’s arrival. An example of how eager they are for care. We’ve seen a variety of ailments. Some include injuries due to aggression or foreign objects stuck in the eye (sticks, bugs, glass) as well as a fair share of cataracts. The equipment that the IVV clinic houses centers around spectacles, cataracts, glaucoma, and the removal of growths. Sometimes, nothing can be done to help a patient. Western medicine has not been able to reach all corners of the world. Despite the fact that in the US we can readily fix a macular hole or retinal detachment, nothing can be done here without the correct equipment. It is heartbreaking to turn away these patients when you know the only limiting factor is geography.  The team- Tracy Sanford, Dr. Matt Wood, Walker Wood, Sanford wood, Dr. Samuel Verkerk, Dr. James "Bud" Tysinger The team- Tracy Sanford, Dr. Matt Wood, Walker Wood, Sanford wood, Dr. Samuel Verkerk, Dr. James "Bud" Tysinger BLOG #1: Our First… This is our first time serving in another country, our first time living with Zambians, our first time “window” shopping in a 3rd world market. Too many firsts to list them all, but definitely our first time working for IVV in their Eye Clinic in Zambia. To describe it in a word, the experience is eye-opening (pun intended). We come from the central part of the US (Nebraska for those that know US geography), and we are quickly realizing just how fortunate we are – maybe taking for granted our education, healthcare, transportation, communications and so much more. When you work in a 3rd world country the differences are readily apparent. However, this experience is enriching in so many ways, making us appreciate our fortune. With that in mind we are embracing the cultural differences to see life through another perspective. The most interesting experience our first day was attending chapel before beginning clinic. This simple daily ritual affords beautiful acapella music and a highly energetic sermon given in English and the dominant language of southern Zambia, Tonga. At this service, in particular the minister introduced our team to the community, and we were welcomed with a hearty laugh as he could not pronounce our names. We will stay a week and are sure to see more firsts. For instance, we are looking forward to our first Zambian meal (Sylvia is a great cook but makes mostly western meals). It is comforting that guest house accommodations are good: there is running water, and yes, you can drink it, and every morning there is a hot shower and hot coffee to start our days off just like home. |

Archives

March 2018

Categories |